Ketamine is sometimes grouped with opioids in public conversation, especially as its use expands in both medical and non-medical settings. This has led to a common question: is ketamine an opioid?

The short answer is no. Ketamine is not an opioid. However, that doesn’t mean it is risk-free. Ketamine affects the brain in ways that can still lead to misuse, dependence, and addiction, particularly outside of medical supervision.

Understanding how ketamine works, how therapeutic ketamine differs from illicit use, and what alternatives exist can help people make safer, more informed decisions about treatment and recovery.

Is Ketamine an Opioid?

Ketamine is not an opioid. It does not belong to the opioid drug class and does not primarily act on opioid receptors in the brain.

Instead, ketamine is classified as a dissociative anesthetic. Its primary mechanism of action involves blocking NMDA receptors, which play a role in pain perception, mood regulation, and learning. While ketamine can indirectly influence opioid pathways and pain signaling, it works very differently from drugs like morphine, heroin, oxycodone, or fentanyl.

This distinction matters because opioids and ketamine carry different risks, effects, and treatment considerations.

How Ketamine Works in the Brain

Ketamine alters perception, mood, and consciousness by disrupting communication between certain brain regions. At lower doses, it can produce dissociative effects, mood changes, and altered sensory perception. At higher doses, it can cause sedation or anesthesia.

Because ketamine affects multiple brain systems at once, its effects can feel powerful and rapid. This is one reason it has gained attention for pain management and certain mental health conditions, but it is also why misuse can escalate quickly.

Therapeutic Ketamine vs. Illicit Ketamine Use

Not all ketamine use looks the same. There is an important difference between medical ketamine treatment and non-medical or illicit ketamine use.

Therapeutic Ketamine

In clinical settings, ketamine may be prescribed or administered for specific purposes such as anesthesia, pain management, or treatment-resistant depression. These treatments are typically:

- Delivered at controlled doses

- Monitored by medical professionals

- Part of a structured treatment plan

- Accompanied by screening and follow-up care

When used appropriately under medical supervision, risks are reduced, though not eliminated.

Illicit or Non-Medical Ketamine

Illicit ketamine is often used recreationally or without medical oversight. This may involve powders, liquids, or pills obtained outside legal channels. In these settings, dosing is unpredictable, purity is unknown, and medical monitoring is absent.

Illicit use carries a much higher risk of adverse effects, dependence, and long-term harm, including bladder damage, cognitive impairment, and psychological dependence.

Can Ketamine Be Addictive?

Yes. Ketamine can be addictive, even though it is not an opioid.

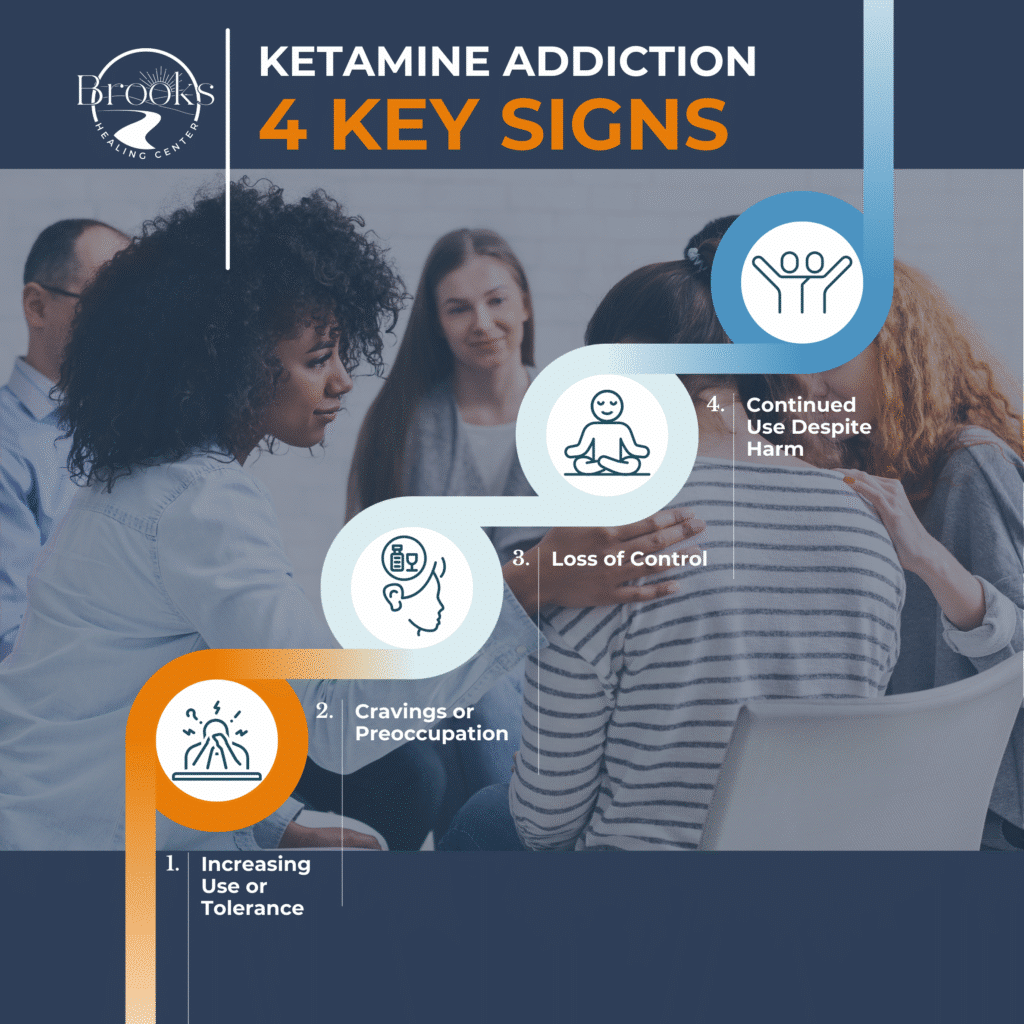

Repeated or high-dose use can lead to tolerance, cravings, and compulsive use. Some people begin using ketamine to manage emotional pain, stress, or trauma and find it increasingly difficult to stop. Over time, misuse can interfere with daily functioning, relationships, and mental health.

Addiction risk tends to increase when ketamine is:

- Used frequently or in escalating doses

- Taken outside medical supervision

- Combined with other substances

- Used as a coping mechanism rather than part of structured care

Risks and Side Effects of Ketamine Use

Ketamine use, especially outside medical settings, is associated with several risks, including:

- Dissociation and confusion

- Anxiety or panic reactions

- Memory and attention problems

- Bladder and urinary tract damage

- Increased risk of accidents or injury

- Psychological dependence

These risks highlight why ketamine should not be viewed as harmless or interchangeable with evidence-based addiction treatment.

Alternatives to Ketamine for Mental Health and Recovery

For individuals concerned about ketamine’s risks or addiction potential, there are both medical and holistic alternatives that may offer safer, more sustainable support.

Medical Alternatives

Depending on individual needs, evidence-based options may include:

- Antidepressant or mood-stabilizing medications

- Medication-assisted treatment for substance use disorders

- Structured psychotherapy such as cognitive behavioral therapy or trauma-focused therapies

- Medically supervised detox and stabilization when substance use is involved

These approaches are supported by clinical research and delivered within regulated healthcare systems.

Holistic and Integrative Approaches

Many people benefit from complementary strategies that support recovery and mental health, such as:

- Mindfulness and meditation practices

- Exercise and movement-based therapies

- Nutrition and sleep support

- Stress-management and emotional regulation skills

- Peer and community support

While holistic approaches are not substitutes for medical care when it is needed, they can play a meaningful role in long-term recovery.

Alternatives to Ketamine: Effectiveness by Diagnosis

While ketamine has shown rapid effects in some conditions, evidence-based alternatives often offer comparable or better long-term outcomes, especially when delivered within regulated healthcare settings.

Important context:

“Efficacy” below refers to clinically meaningful symptom improvement, not cure. Outcomes vary based on severity, comorbid substance use, adherence, and quality of care.

| Diagnosis | Treatment Option | Estimated Response / Improvement Rate | Notes on Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment-Resistant Depression (TRD) | Ketamine (clinical setting) | ~50–70% short-term response | Rapid effects but often transient; relapse common without ongoing care |

| Antidepressant medication (SSRIs/SNRIs) | ~40–60% | First-line for many; slower onset | |

| Psychotherapy (CBT, IPT) | ~45–60% | Comparable to medication over time | |

| TMS (Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation) | ~50–65% | Non-invasive, FDA-cleared | |

| ECT | ~70–90% | Highest efficacy; more intensive | |

| Major Depressive Disorder (non-TRD) | Antidepressants | ~50–65% | Strong evidence base |

| Psychotherapy | ~50–65% | Long-term durability | |

| Exercise-based interventions | ~30–50% | Best as adjunctive treatment | |

| Anxiety Disorders | CBT / exposure-based therapy | ~60–80% | Gold standard for anxiety |

| SSRIs/SNRIs | ~60–70% | First-line pharmacologic option | |

| Ketamine | Limited, inconsistent | Not FDA-approved for anxiety | |

| Mindfulness-based therapy | ~40–60% | Adjunctive benefit | |

| PTSD | Trauma-focused psychotherapy (EMDR, CPT, PE) | ~60–80% | Strongest evidence |

| SSRIs (sertraline, paroxetine) | ~50–60% | FDA-approved options | |

| Ketamine | ~40–60% (short-term) | Research ongoing; durability unclear | |

| Somatic therapies (adjunct) | Variable | Supportive, not standalone | |

| Chronic Pain | Multimodal pain management | ~50–70% | Best outcomes with integrated care |

| Non-opioid medications | ~40–60% | Condition-specific | |

| Ketamine (pain protocols) | ~50–70% | Typically inpatient or specialty care | |

| Substance Use Disorders | Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) | ~60–80% reduction in relapse | Strong mortality benefit |

| Behavioral therapies | ~40–60% | Improves long-term outcomes | |

| Ketamine | Experimental | Not standard of care | |

| Suicidal Ideation | ECT | ~80% rapid reduction | Emergency-level intervention |

| Inpatient stabilization + therapy | ~60–75% | Depends on follow-up care | |

| Ketamine | ~50–70% rapid reduction | Short-lived without continuation |

Ketamine and Addiction Treatment Considerations

Ketamine is sometimes discussed as a tool for mental health or addiction recovery, but it is not a cure-all. Its use requires careful screening, clear boundaries, and ongoing monitoring. For people with a history of substance use disorders, the risks many times outweigh the potential benefits.

Evidence-based addiction treatment focuses on safety, long-term outcomes, and individualized care rather than quick or unregulated solutions.

Final Thoughts About Ketamine

Ketamine is not an opioid, but it is still a powerful psychoactive substance with real risks. The distinction between therapeutic ketamine and illicit use is critical, especially when considering addiction potential and long-term health.

Anyone exploring treatment options should weigh legality, safety, personal history, and evidence-based alternatives. Recovery and mental health care are not one-size-fits-all, and the safest path forward is one grounded in medical guidance, structured support, and informed decision-making.

Frequently Asked Questions About Ketamine Therapy & Addiction

Is ketamine an opioid?

No. Ketamine is not an opioid. It is classified as a dissociative anesthetic and works primarily by blocking NMDA receptors in the brain. While ketamine can affect pain perception and may indirectly interact with opioid pathways, it does not act on opioid receptors in the same way drugs like morphine, oxycodone, or fentanyl do.

Does ketamine therapy get you high?

Therapeutic ketamine is not intended to produce a recreational “high,” but it can cause temporary dissociation or altered perception, especially during treatment sessions. In medical settings, dosing is carefully controlled and monitored to reduce risk. Illicit ketamine use, by contrast, is often pursued specifically for euphoric or dissociative effects and carries much higher risks.

Does ketamine show up on a 12-panel drug test?

Standard 12-panel drug tests do not typically test for ketamine. However, specialized or expanded drug panels can detect it. Ketamine may also be identified through blood, urine, or hair testing if specifically ordered.

How long does ketamine last?

The acute effects of ketamine generally last 30 minutes to 2 hours, depending on dose and method of use. Some aftereffects, such as fatigue, mood changes, or dissociation, may persist for several hours or longer.

Is ketamine a horse tranquilizer?

Ketamine is sometimes referred to as a “horse tranquilizer” because it is used in veterinary medicine for anesthesia in large animals. However, it is also a legitimate medication used in human medical care, including surgery and certain supervised mental health treatments. The label is misleading and oversimplifies how the drug is used.

How long does ketamine stay in your system?

Ketamine is usually detectable in urine for 1 to 3 days after use, though this can vary based on dose, frequency of use, metabolism, and testing method. Chronic or heavy use may extend detection times.

Is ketamine a psychedelic?

Ketamine is not a classic psychedelic like LSD or psilocybin. It is considered a dissociative anesthetic, though it can produce psychedelic-like effects at certain doses. Its mechanism of action is different from traditional psychedelics.

Is ketamine legal in Tennessee?

Yes, ketamine is legal in Tennessee when prescribed or administered by a licensed medical provider. It is classified as a Schedule III controlled substance, meaning it has accepted medical uses but also potential for misuse. Non-medical possession or distribution is illegal.

Can you overdose on ketamine?

Yes. Ketamine overdose is possible, particularly when used in high doses or combined with other substances such as alcohol, opioids, or benzodiazepines. Overdose risks include slowed breathing, loss of consciousness, cardiovascular complications, and, in severe cases, death.

Sources

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (2023, October 10). FDA warns patients and health care providers about potential risks associated with compounded ketamine. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/fda-warns-patients-and-health-care-providers-about-potential-risks-associated-compounded-ketamine

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2024, April 9). Ketamine (NIH). https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/ketamine

- Sanacora, G., Frye, M. A., McDonald, W., Mathew, S. J., Turner, M. S., Schatzberg, A. F., Summergrad, P., Nemeroff, C. B., & American Psychiatric Association (APA) Council of Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments. (2017). A consensus statement on the use of ketamine in the treatment of mood disorders. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(4), 399–405. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28249076/

- McIntyre, R. S., Rodrigues, N. B., Lee, Y., Lipsitz, O., Subramaniapillai, M., Gill, H., Nasri, F., Majeed, A., Lui, L. M. W., & Ho, R. (2021). Synthesizing the evidence for ketamine and esketamine in treatment-resistant depression: An international expert opinion on the available evidence and implementation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(5), 383–399. https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20081251

- Janssen-Aguilar, R., & colleagues. (2025). Role of ketamine in the treatment of substance use disorders. Discover Mental Health. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2949875925000840

- Van Amsterdam, J., Nabben, T., Keiman, D., Haanschoten, G., & Korf, D. J. (2022). Harm related to recreational ketamine use and its relevance for the clinical use of ketamine. Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology, 15(3), 323–333. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14740338.2021.1949454

- Anderson, D. J., & colleagues. (2022). Ketamine-induced cystitis: A comprehensive review of the urologic effects of recreational ketamine use. International Neurourology Journal. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9476224/

- Tennessee General Assembly. (2024). Tennessee Code Annotated § 39-17-410: Controlled substances in Schedule III. https://law.justia.com/codes/tennessee/title-39/chapter-17/part-4/section-39-17-410/

- Tennessee Secretary of State. (2023, January 1). Rules of the Tennessee Department of Health: Controlled substances schedules (0940-06-01). https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/rules/0940/0940-06/0940-06-01.20230101.pdf

- U.S. Department of Justice, Drug Enforcement Administration. (n.d.). Controlled substances schedules. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/schedules/

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021). TIP 63: Medications for opioid use disorder. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/tip-63-medications-opioid-use-disorder